National Treasure Hall

The Eight Kinds of Mythological Beings(National Treasures)

Now housed in the National Treasure Hall, this group of statues depicts the Eight Kinds of Mythological Beings, figures from Indian mythology that were incorporated into the Buddhist pantheon to serve as protectors of the Buddha and his teachings. As a set, they appear in various Buddhist scriptures, among them the Sutra of the Golden Light, a text highly valued in the Nara Period (710–794) for its state-protecting powers. Their presence on the altar of a Buddhist temple hall reflects the belief that the Buddha’s teachings are intended not merely for humans, but for all other sentient beings as well.

Sculpted between 733 and 734, these images were originally enshrined in Kohfukuji’s Western Golden Hall, which was lost to fire a total of four times, most recently in 1717. A key reason for their survival is the material of which they are made: All eight images were manufactured using the hollow-core dry-lacquer technique, in which lacquer-soaked fabric is layered onto a clay core that is removed after the lacquer has hardened. The hollow core is then reinforced with a light wooden frame that prevents warping, and facial features and other details modelled using a paste made of lacquer and sawdust before the image is painted and gilded. The resulting sculptures are incredibly light (the eight statues weigh between 10 and 15 kilograms each), making them easy to move to safety in case of fire.

The eight sculptures are now identified as Ashura, Gobujō, Sakara, Kendatsuba, Kinnara, Kubanda, Hibakara, and Karura. In fact, however, it is likely that they originally represented a different group of beings commonly encountered in Buddhist scriptures: asuras (demigods or titans), devas (gods), nāgas (snakes or dragons), garuḍas (enormous snake-eating birds), yakṣas (spirits of the dead), gandharvas (ghostly musicians), kiṃnaras (heavenly musicians), and mahoragas (snake spirits).

One unique aspect of this set is that the images of the Ashura, Gobujō, Sakara, and Kendatsuba have the faces of young boys. Scholars have suggested that this reflects the wishes of the patroness who sponsored their construction, Empress Kōmyō (701–760), the daughter of Kohfukuji’s founding patron, Fujiwara no Fuhito (659–720).

The Ten Great Disciples (National Treasures)

These exquisite images from the Nara period (710–794) are part of a set that originally depicted ten especially famous disciples of the historical Buddha, Shaka Nyorai (Skt. Śākyamuni).

Sculpted between 733 and 734, and enshrined in the Western Golden Hall at the time of its consecration in 734, all ten images survived four subsequent fires that destroyed the building, including the most recent in 1717. A key reason for their survival is the hollow-core dry-lacquer technique with which they were constructed, which results in images that are incredibly light (the extant statues weigh between 10 and 15 kilograms each), making them easy to move to safety in case of fire.

The images display a variety of different facial expressions and hand gestures, and portray Buddhist monks of various ages, with the older ones having more wrinkles and a greater number of folds in their robes. Rather than historical figures, these disciples are best understood as archetypes that represent various monastic ideals, such as excellence in meditation, debate, or preaching.

The six images that remain at Kohfukuji are now identified as Mokkenren, Sharihotsu, Subodai, Kasen’en, Furuna, and Ragora, but the extent to which these labels reflect their original identities is uncertain. The closed eyes of the image now identified as Ragora (Skt. Rāhula), for example, suggest it may originally have been intended to portray the blind monk Aniruddha, while the youthful image of Subodai (Skt Subhūti) closely matches canonical descriptions of the disciple Ānanda.

The wooden frame of one of the other sculptures is now in the collection of the Tokyo University of the Arts. One image is known to have been lost when the Okura Museum of Art in Tokyo burned down in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. The whereabouts of the remaining two statues are unknown.

Relief Carvings of the Twelve Heavenly Generals (National Treasures)

This set of carvings depicting the Twelve Heavenly Generals was originally housed in the Eastern Golden Hall. Scholars believe it was mounted on the faces of the seat of the main icon of the hall, Yakushi Nyorai, the Buddha Master of Medicine. The images, which date to the eleventh century, are considered masterpieces of itabori wooden relief carving.

The Twelve Heavenly Generals serve as guardians of Yakushi Nyorai, and are often depicted with fierce, angry faces. These carvings, however, are famous for their humorous expressions, as well as for the incredible sense of depth that their sculptors managed to convey using boards of Japanese Cypress (Hinoki) that are only three centimeters thick. The figures all strike different poses, with some performing exaggerated gestures reminiscent of kabuki actors and others portrayed in the frontal, static manner associated with religious icons.

Since the iconography of the Twelve Heavenly Generals was never fixed, and the names of the images are later attributions, the original identity of each of the images is uncertain. Their current display case seeks to replicate the original configuration of the images on the front and side faces of the seat of Yakushi Nyorai. The arrangement is based on a study of their postures, hand gestures, and facial expressions.

Head of Yakushi Nyorai (National Treasure)

Dated to 685, this cast copper alloy head formerly belonged to a sculpture of the Buddha Master of Medicine (Jp. Yakushi Nyorai) that was originally enshrined at Yamadadera Temple in Asuka, a town about 20 kilometers south of the city of Nara, and the capital of Japan at the time of the image’s construction.

After the Kohfukuji Temple complex was destroyed by troops under Taira clan commander Taira no Shigehira (1158–1185) in 1181, the priests of Kohfukuji removed the image from Yamadadera, carried it to Kohfukuji, and installed it in the reconstructed Eastern Golden Hall, where it served as the main icon for more than two centuries.

Although it was rescued from a fire that destroyed the hall in 1356, it was trapped inside the building when the Eastern Golden Hall was consumed by fire yet again in 1411. As the copper statue melted in the blaze, the head broke off and fell to the ground, breaking off the ear lobe and deforming the left side of the face. Judged to be beyond repair, the head was ultimately placed inside the throne of the statue’s replacement, which was consecrated in 1415, and remains the principal image of the hall to this day. Thereafter, the head’s existence was forgotten until 1937, when it was rediscovered during repairs to the building. An inscription on wooden boards included with the head told the story of the fire of 1411, enabling researchers to establish its provenance.

Since most surviving Buddhist images from the Hakuhō Era (latter half of seventh century to early eight century) are miniature statues that can only be dated on the basis of style, the significance of the discovery of even a part of a full-sized Buddha image whose date of construction is known for certain can hardly be overstated. On the basis of its historical significance and artistic value, the head therefore became one of the few Buddhist image fragments to be declared a National Treasure.

Shaka Nyorai (Important Cultural Property)

This statue depicts the founder of Buddhism, Shaka Nyorai (Skt. Śākyamuni), a historical figure who attained awakening and vowed to save sentient beings in north-eastern India in the fifth century BC.

The image was carved from blocks of katsura wood that were then assembled and covered with lacquer and gold leaf. While its origin is unclear, its round face, peaceful expression, and shallowly carved robes are hallmarks of the style of the Heian Period (794–1185), and particularly resemble images carved by the innovative Buddhist sculptor Jōchō (d. 1057). The mandorla that originally stood behind the image has been lost, and the throne on which it sits is a later addition.

The image’s right hand is lifted with the palm toward the viewer in the gesture of dispelling fear (semui-in), while the left rests on its left leg with the palm facing up forming the gesture of granting wishes (yogan-in). The webs between the fingers of both hands, a symbol of the Buddha’s desire to scoop up and rescue as many sentient beings as possible, are particularly prominent on this statue.

Transformation Buddha and Flying Apsara (Important Cultural Properties)

Dated to the Kamakura Period (1185–1333), these carvings depict a seated Buddha and two apsara, flying female celestial spirits widely encountered in Buddhist mythology. Although their provenance cannot be established conclusively, scholars believe that the renowned Buddhist sculptor Unkei (1150–1223) supervised their creation, and that they were originally attached to the mandorla of the image of Shaka Nyorai that was the principal icon of Kohfukuji’s Western Golden Hall. It seems likely that they were removed from the mandorla in an effort to rescue them from the fire that engulfed this hall in 1717.

Thousand-Armed Kannon (National Treasure)

This 5.2-meter-tall image of the Bodhisattva Kannon was the principal icon of the Kohfukuji Temple refectory from the thirteenth to the nineteenth centuries. Originally erected in 744, the refectory was lost to fire twice, most recently during the Burning of the Southern Capital (Nara) by troops under Taira clan commander Taira no Shigehira (1158–1185). The reconstructed building lasted for centuries, only to be torn down in 1874 in the midst of the anti-Buddhist persecutions of the early Meiji Period (1868–1912). Fortunately, its colossal image of the Thousand-armed Thousand-eyed Kannon (Skt. Sahasrabhuja-sahasranetra Avalokitēśvara) escaped destruction, and was moved back to its original location once the Kohfukuji National Treasure Hall had been erected on top of the foundation of the refectory in 1959.

The Bodhisattva Kannon is the symbolification of Buddhist compassion. The Thousand-armed Thousand-eyed form of Kannon (which literally translates to “He who perceives the sounds of the world”) gives visual shape to this idea of compassion by creating a narrative in which Kannon hears the cries of sentient beings, swiftly locates them with eyes that gaze in all directions (the image actually has a total of twenty-six eyes in thirteen heads) and provides whatever help or succor they might need with the tools and weapons he holds in his forty-two hands (which include two primary hands joined in prayer and forty secondary hands, each of which stands for twenty-five hands, thereby bringing the total to one-thousand).

A year after the loss of the original principal icon of the refectory during the conflagration of 1181, plans for a replacement image were drawn up, and the sculptor Seichō was tasked with overseeing its construction. Sometime thereafter, this project appears to have ground to a halt. Due to a lack of historical records, it is unknown when work on the statue resumed and it was finally completed. Fortunately, a number of items were deposited inside the sculpture, among them a copy of the Heart Sutra bearing the date of 1217 and a copy of the Dhāraṇī of the Thousand-armed Thousand- eyed Avalokitēśvara written in Sanskrit that bears a date of 1229. Taken together with other items deposited in the statue, these two manuscripts give some indication of the dates of the resumption and ultimate completion of the construction process, and bear witness to an unusually long and arduous fundraising campaign that came to involve a large number of patrons.

Kongō Rikishi(National Treasures)

The Kongō Rikishi (Skt. Vajrapāṇi) are mythological warriors bearing vajra, Indian weapons that symbolize thunderbolts. Dating to the early Kamakura Period (1185–1333) and created by a sculptor of the Kei School, this pair of sculptures are masterpieces of the realism, dramatic movement, and power that are hallmarks of twelfth- and thirteenth-century Japanese Buddhist sculpture. Inlaid crystal eyes, wind-whipped robes, bulging muscles, and protruding veins all reinforce their lifelike appearance.

The statue on the left has its mouth wide open to symbolize the sound a, the sound of the first letter of the Sanskrit alphabet, and, philosophically, the realm of the absolute. The right-hand statue has its mouth tightly closed to symbolize the sound hūṃ, the sound of the final letter of the alphabet and the realm of phenomena. Together, these symbolize the beginning and the end of all things, or, in essence, the entire universe.

Images of the Kongō Rikishi are most commonly encountered as guardian figures enshrined on both sides of Buddhist temple gates. During the Nara Period (710–794), however, they were also installed on the edges of the altars found in temple halls. This pair of statues, carved from joined wood blocks, was originally enshrined in Kohfukuji’s Western Golden Hall, and was carved as a replacement for a Nara-period pair of sculptures that was lost when the hall burned down in 1181.

Ryūtōki and Tentōki (National Treasures)

These humorous and highly unusual thirteenth-century sculptures portray a pair of impish demons. Such demon figures are usually encountered being trampled underfoot by Buddhist guardian figures such as the Four Heavenly Kings. Here, however, they are depicted as converts to Buddhism who bear lanterns offering light to the Buddha. The sculptures were originally enshrined on the central altar of the Western Golden Hall.

The figure known as Ryūtōki (“Demon with Dragon and Lantern”) was carved in 1215, and is known to be the work of Kōben (dates unknown), the son of the famous Buddhist sculptor Unkei (1150–1223). It is unclear whether Kōben also sculpted the image called Tentōki (“Demon Holding a Lantern Aloft”), but it is clearly the work of a sculptor of the Kei School, and dates to the same period. One unusual feature of the Ryūtōki image is the use of materials other than wood. The bristling eyebrows are cut from sheets of copper, the fangs are made of rock crystal, and the fins on the back of the dragon that winds around its body are made of animal hide. Both images also feature inlaid crystal eyes that heighten their sense of vivid presence even further.

Head of Shaka Nyorai (Important Cultural Property)

This large wooden head covered in lacquer and bearing traces of gold leaf formerly belonged to the principal icon of the Western Golden Hall. It depicts the founder of Buddhism, Shaka Nyorai (Skt. Śākyamuni), a historical figure who attained awakening and vowed to save sentient beings in north-eastern India in the fifth century BC. The image was carved by the renowned Buddhist sculptor Unkei (1150–1223) around the year 1189 as a replacement for an eighth-century image that had been lost to fire eight years earlier. When the Western Golden Hall caught fire once again in 1717, there was no time to move the image in its entirety. Instead, the head, hands (not on display) and a Transformation Buddha and two Flying Apsara originally mounted on the mandorla were wrenched off and rescued separately.

Shaka is depicted with full cheeks and lips, gracefully arched eyebrows, and large pierced earlobes. His head covered with stylized spiral cones (Jp. rahotsu) that symbolize the stubble of the shaved head of a renunciant. A unique feature of this head is that it lacks a “dot” on its forehead. Known in Sanskrit as an ūrṇā, this raised dot is actually a tightly curled white hair from which the Buddha emits light to announce that he is about to preach. According to temple lore, when the sculptor of the original eighth-century image was about to place a standard crystal ūrṇā on the head of the statue, the forehead suddenly split open and light poured out of the image. In awe, he abandoned his plan for the artificial ūrṇā, and Unkei, who created the image’s replacement image, followed suit.

Enshrined Image of Miroku Bosatsu (Important Cultural Property)

This intricately executed statue depicts Miroku Bosatsu, or, in Sanskrit, the Bodhisattva Maitreya. According to Buddhist tradition, Miroku is the immediate successor of the historical Buddha Shaka (Skt. Śākyamuni), and will be born in this world 5.67 billion years from now to become its next Buddha. Here he is depicted as a gorgeously dressed “Buddha to be,” who wears an expression of meditative tranquility on his face and sits on a lotus throne with his left leg dangling towards the ground. It is likely that this posture is meant to convey that he has not yet assumed the throne of a fully awakened Buddha, but instead lingers in this world to save sentient beings from suffering. The image’s right hand is lifted with the palm toward the viewer in the gesture of dispelling fear (semui-in), while the left rests on its left leg with the palm facing up forming the gesture of granting wishes (yogan-in).

The image was carved from wood during the Kamakura Period (1185–1333) and is remarkably well preserved. Backed by a radiant golden mandorla, the figure is adorned with elaborate robes and jewelry, including a pendant shaped like an eight-spoked wheel that symbolizes Wheel of the Dharma, another term for the Buddha’s teaching.

The rectangular shrine (zushi) housing the statue protected it from light, pests, and other damage over the centuries. The interior is gorgeously decorated, and features a canopy composed of images of celestial musicians (Skt. Apsara) that hang down from the shrine’s roof to encircle the image’s head. The doors are painted with portraits of the patriarchs of the Hossō School, as well as Monju Bosatsu (Skt. Mañjuśrī), Yuima Koji (Skt. Vimalakīrti) two of the Four Heavenly Kings, and the Wisdom-kings (Jp. Myōō) Fudō and Dairin.

Votive Offerings Deposited in the Foundation of the Central Golden Hall(National Treasures) National Treasure Hall

Prior to the construction of Kohfukuji’s original Central Golden Hall, which was dedicated in 714, a series of rituals were performed to alert the earth deities of the use of their land, and ask for their protection of the newly erected building.

As part of these rites, almost 2,000 precious objects representing the Seven Treasures (gold, silver, pearl, rock crystal, amber, agate, and beryl) were buried beneath the location of the central altar. These objects include prayer beads made of rock crystal, amber, and agate; vessels made of silver and gilded copper alloy; hexagonal and round cylinders made of rock crystal and amber that appear to have been used as ornaments or amulets; decorations made out of sheets of silver stenciled with arabesque designs; wadō kaichin and kaigen tsūhō coins; gilded copper alloy and silver knives; and mirrors made of copper alloy.

Deposits of votive offerings have been unearthed from the foundation of the Central Golden Hall a total of three times. Those discovered in 1874 are held by the Tokyo National Museum, while those dug up in 1884 are stored at Kohfukuji. Due to their artistic value and historical significance, these exquisite objects, many of which were imported from Tang-dynasty China, have been designated Japanese National Treasures. A further batch of deposits was unearthed in 2001, and is also held by Kohfukuji.

Kagenkei Gong and Stand (National Treasure)

This rare musical instrument was placed on the altar of Kohfukuji’s Western Golden Hall when the building was dedicated in 734. Originally called the Golden Drum, it formed part of a tableaux depicting a scene from the Scripture of the Golden Light, the Buddhist sutra on which the layout of the images in the hall was based.

By the Muromachi Period (1336–1573), the instrument had come to be known as Kagenkei, or “Gong from Kagen,” in reference to China’s Huayuan region, which is pronounced Kagen in Japanese. Located in the modern-day Yaozhou district of Shaanxi Province, Huayuan was famous as a site where the stone plates used to make such gongs were quarried. Ironically, the current gong, a replacement dating to the Kamakura period (1185–1333), is made not of stone, but of metal.

Made of cast copper alloy, the stand of the instrument consists of a hexagonal pole mounted on the back of a squatting lion that is a later addition dating to the Heian Period (794–1185). Two pairs of male and female dragons curl around the top end of the pole, gazing outward. The gong, which would originally have been gilded, is suspended between their curving bodies. The level of detail evident in the casting suggests that this piece is not of native manufacture, but was cast in Tang-dynasty China (618–907), and brought to Japan during the Nara period (710–794) instead.

Lantern(National Treasure) National Treasure Hall

Cast in 816, this copper-alloy lantern is the second-oldest datable lantern in Japan (the oldest being the lantern in front of the Great Buddha Hall of Tōdaiji Temple). Kohfukuji’s lantern was installed in front of the Southern Round Hall three years after the building’s completion in 813, and originally housed an oil lamp burning day and night as an offering to the Buddha. Although the top ornament was lost and the lower parts of the lantern were replaced over the centuries, it is still the only remaining artifact from the early days of the Southern Round Hall.

Due to its graceful shape and elegant proportions, this lantern was copied frequently, and eventually became the prototype of the “Southern Round Hall Type,” examples of which can now be found at Buddhist temples all over Japan. The original chimney panels are inscribed with a text composed by one of the most famous monks in Japanese history, Kūkai, better known by his posthumous title Kōbō Daishi (774–835), the founder of the Shingon Sect of Japanese Buddhism.

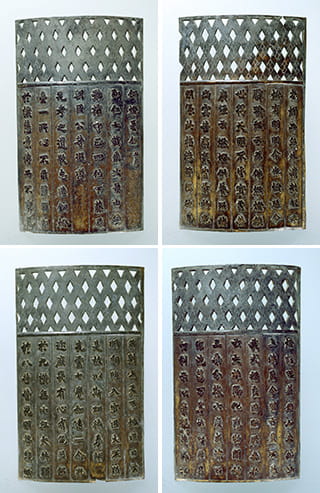

Inscribed Lantern Chimney Panels (National Treasures)

Cast in 816, these copper alloy chimney panels used to be attached to the lantern that stood in front of the Southern Round Hall. Of the six original panels, four survive today. They are inscribed with a text composed by one of the most famous monks in Japanese history, Kūkai, better known by his posthumous title Kōbō Daishi (774–835), the founder of the Shingon Sect of Japanese Buddhism. The text itself draws on a number of Buddhist Scriptures to extoll the virtue of the act of offering light, which is equated to spreading the Buddhist teaching to save the sentient beings of the world. The calligraphy, arranged in seven columns of nine characters per panel, was written in the style of the legendary calligrapher Wang Xizhi (303–361) by the courtier Tachibana no Hayanari (782–844), himself known as one of the three great calligraphers of Japanese history. Since another one of these three was Kūkai himself, this inscription is the only existing work in which two of three great calligraphers collaborated.

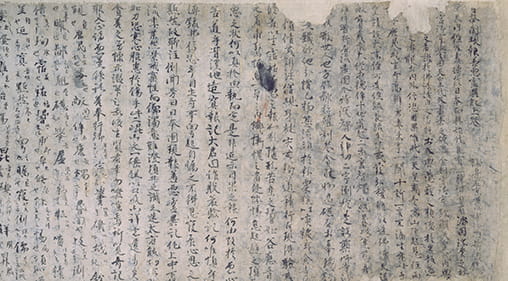

Nihon Ryōiki(National Treasure) National Treasure Hall

Dated to 904, this manuscript is the oldest extant fragment of a work called the Nihon Ryōiki, or Record of Wondrous Events in Japan. Written by the monk Kyōkai sometime between 787 and 824, the Nihon Ryōiki is a collection of 116 tales illustrating the Buddhist teaching that good deeds lead to good results, and bad ones to bad results. The work is famous as the oldest anthology of setsuwa, a genre of folktales, myths, and legends that frequently carry a religious or moral message.

Five fragmentary manuscript copies of the Nihon Ryuichi are extant, of which the oldest two —including this one— are designated National Treasures.

Bonten and Taishakuten (Important Cultural Properties)

Dating to the Kamakura period (1185–1333), these paired wooden images of Bonten and Taishakuten depict gods from the Indian religious pantheon that were incorporated into Buddhism as tutelary deities and guardian figures. Bonten, here depicted holding a lotus flower, is derived from the Indian creator deity Brahmā. Taishakuten, portrayed wearing armor and holding a scroll, is based on Indra, the king of the heavens in early Indian mythology, and a deity associated especially with lightning and war.

Both statues were carved in the early thirteenth century, and were originally enshrined in the Western Golden Hall on both sides of the principal icon, Shaka Nyorai (Skt. Śākyamuni). Stylistically, they represent a Japanese adaptation of twelfth-century (Song-dynasty) Chinese models. Evidence of this is seen in the upturned and elaborately decorated tips of the shoes, and the scalloping along the collars and cuffs of the robes.